Use-by dates on milk containers are to be scrapped in favour of the classic “sniff test”, according to numerous news outlets this week, under plans being drawn up by the food waste charity WRAP. By the end of the year, so we’re told (e.g. here and here and here), we’ll all be relying on our noses rather than dates, in an effort to save a staggering 500 million pints poured down the sink in Britain each year.

An interesting idea? Common sense, even? Perhaps, except that it’s simply not true.

The WRAP Report

The charity’s latest report on consumer food waste, published on the 27th February, is a comprehensive 37-page document outlining recent developments in food packaging and labelling. It notes several positive developments, such as supermarkets supplying smaller bags of salad. And it lists recommendations that might help to further reduce waste, such as changing labelling from “use by” to “best before” for certain products, including milk.

But there is no mention of sniff tests anywhere in their report, nor in the press release accompanying it, nor is there even the slightest whiff of any such recommendation.

Sniffing out Ground Zero

Intrigued, I scented out the source of the story. It turns out that the WRAP report was covered in an excellent article in the Times on the day of its release. The article does highlight the particular case of milk, describing how labels now advise consumption within a much shorter time period than they used to. But there is no mention of sniff tests here either – only the actual WRAP recommendations.

However, the story was accompanied by an amusing commentary – with the tagline “Your nose knows best” - which played with the implications of the recommendations. From there, so it would seem, the story has spread like eau de farmyard on a strong summer breeze, with a bullish base note of Chinese whispers.

So there is not, in fact, any such proposal to leave us relying solely on our sense of smell for detecting spoiled milk, or any other kind of food. But would such a test be viable, even if there were?

Would a Sniff Test work?

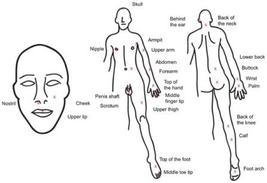

Many of us will have often smelled the milk bottle before using it, and occasionally we will have chosen not to use it because of its smell. Indeed, it is thought that finding and assessing potential food is one of the three main functions of our sense of smell – the other two being related to avoiding infectious matter in the environment and finding partners.

The unpleasant aroma of spoiled milk, in particular, arises due to the action of proliferating bacterial populations which occur even in pasteurised milk. The smell itself is actually a cocktail of numerous volatile odour compounds, like acetaldehyde, 3-methyl-1-butanol, and acetic acid. These can smell quite good on their own – acetaldehyde has a fruity smell while methyl butanol is found in the aroma of truffles – but together they form a rather less appetising mixture. Pasteurised milk would likely have to curdle to do you any serious harm – and then you would usually be able to see it quite clearly, let alone smell it – but nonetheless the sniff test could clearly be a useful warning signal.

But having to rely on a sniff test alone, for any food product, would be unfortunate. For one thing, our sense of smell varies from day to day and week to week. While known changes in smell sensitivity across a woman’s menstrual cycle might be unlikely to interfere with the detection of spoiled milk, waking up with a stuffy head cold just might.

More importantly, a significant proportion of the population suffer from olfactory deficits ranging from mild or moderate impairment to total loss of the sense of smell. Several studies suggest rates of clinical olfactory impairment to be around one in five of the population and particularly high in those of older age, especially men. Often, people are unaware they even have a deficit, possibly because odour is often subconsciously processed in the brain. Furthermore, in up to 4% of the population with congenital anosmia (that is, have no sense of smell since birth), this is often noticed only around the early teenage years.

In short, there are vulnerable groups of the population among whom there is both a deficit and a lack of awareness of that deficit, who would be at risk.

So scrapping labelling on milk altogether is not what WRAP is recommending, contrary to many headlines. But even if it were, it would not be a great idea. The nose might indeed know best, but only when it’s in fine working order.

An interesting idea? Common sense, even? Perhaps, except that it’s simply not true.

The WRAP Report

The charity’s latest report on consumer food waste, published on the 27th February, is a comprehensive 37-page document outlining recent developments in food packaging and labelling. It notes several positive developments, such as supermarkets supplying smaller bags of salad. And it lists recommendations that might help to further reduce waste, such as changing labelling from “use by” to “best before” for certain products, including milk.

But there is no mention of sniff tests anywhere in their report, nor in the press release accompanying it, nor is there even the slightest whiff of any such recommendation.

Sniffing out Ground Zero

Intrigued, I scented out the source of the story. It turns out that the WRAP report was covered in an excellent article in the Times on the day of its release. The article does highlight the particular case of milk, describing how labels now advise consumption within a much shorter time period than they used to. But there is no mention of sniff tests here either – only the actual WRAP recommendations.

However, the story was accompanied by an amusing commentary – with the tagline “Your nose knows best” - which played with the implications of the recommendations. From there, so it would seem, the story has spread like eau de farmyard on a strong summer breeze, with a bullish base note of Chinese whispers.

So there is not, in fact, any such proposal to leave us relying solely on our sense of smell for detecting spoiled milk, or any other kind of food. But would such a test be viable, even if there were?

Would a Sniff Test work?

Many of us will have often smelled the milk bottle before using it, and occasionally we will have chosen not to use it because of its smell. Indeed, it is thought that finding and assessing potential food is one of the three main functions of our sense of smell – the other two being related to avoiding infectious matter in the environment and finding partners.

The unpleasant aroma of spoiled milk, in particular, arises due to the action of proliferating bacterial populations which occur even in pasteurised milk. The smell itself is actually a cocktail of numerous volatile odour compounds, like acetaldehyde, 3-methyl-1-butanol, and acetic acid. These can smell quite good on their own – acetaldehyde has a fruity smell while methyl butanol is found in the aroma of truffles – but together they form a rather less appetising mixture. Pasteurised milk would likely have to curdle to do you any serious harm – and then you would usually be able to see it quite clearly, let alone smell it – but nonetheless the sniff test could clearly be a useful warning signal.

But having to rely on a sniff test alone, for any food product, would be unfortunate. For one thing, our sense of smell varies from day to day and week to week. While known changes in smell sensitivity across a woman’s menstrual cycle might be unlikely to interfere with the detection of spoiled milk, waking up with a stuffy head cold just might.

More importantly, a significant proportion of the population suffer from olfactory deficits ranging from mild or moderate impairment to total loss of the sense of smell. Several studies suggest rates of clinical olfactory impairment to be around one in five of the population and particularly high in those of older age, especially men. Often, people are unaware they even have a deficit, possibly because odour is often subconsciously processed in the brain. Furthermore, in up to 4% of the population with congenital anosmia (that is, have no sense of smell since birth), this is often noticed only around the early teenage years.

In short, there are vulnerable groups of the population among whom there is both a deficit and a lack of awareness of that deficit, who would be at risk.

So scrapping labelling on milk altogether is not what WRAP is recommending, contrary to many headlines. But even if it were, it would not be a great idea. The nose might indeed know best, but only when it’s in fine working order.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed